To use concentration bounds or anti-concentration bounds, that is the question?

In one of my previous posts reviewing the CS5330 course, I explained how many randomized algorithms exploit concentration bounds, in particular the chernoff bound. Up-till my third year I was under the impression that why would we ever want to argue in the reverse way? Doesnt make sense right, why would would you want to decrease the odds of a good event?

Well turns out, in some cases, anti-concentration bounds are also useful. I will be sharing two examples in this post, first one I encountered as a TA for CS4231 - Parallel and Distributed Algorithms course, which is in the consensus setting. Second one, I came across in my final year research thesis.

Problem 1

(Credits: Rephrased from one of the course examination questions set by Prof. Haifeng Yu for CS4231)

Let me first give the setup of the well-known classical consensus problem.

You are given $N$ nodes, labelled from $1$ to $N$. Each node originally holds a binary value (say $b_i$), i.e. either $0$ or $1$. All the nodes want to come to consensus on a common value, i.e. $0$ or $1$. The method of communication between these nodes is asynchronous pair-wise.

In Asynchronous channels there is no gaurantee that a message from node $a$ to node $b$ will be at most $k$-times slower than the message from say node $c$ to node $d$, for any $k$. The messages between a given pair of nodes will come in-order for sure though. Easiest way to digest the asynchronous model idea is, that you have no easy way to say that the message has timed-out or got dropped since there is no well defined upper-bound. Also running rounds-based algorithms becomes tricky in this setting.

Besides the communication setting, you want to satisfy three basic conditions of consensus which are as follows:

- Agreement: All the non-faulty nodes should agree on a common value

- Validity: If all the non-faulty nodes have the same initial value (i.e. $b_1 = b_2 = \dots = b_n$), then the agreed upon value by all the non-faulty nodes should be that one.

- Termination: All non-faulty nodes should terminate and eventually decide on a value

So well if no node is faulty, then this sounds trivial right, everyone just sends their original value to one another and they look at it and decide on a common value. They could use a simple vote-majoirty or max of all values and be done. Notice, they cant do something trivial like always decide on value $0$, because the Validitiy condition will break if $b_1 = b_2 = \dots = b_n = 1$ in this case.

So now comes the interesting bit in this setting. At most one node can be failed at any abitrary point of time during its algorithm.

And think of a devil (aka strong-adversarial model) looking over the algorithm and the message communication model which decides to fail a node at the most inconvinient time for your algorithm. This devil can enforce the worst case scheduling in the asynchronous model. Now how do these nodes come to consensus? Well the FLP theorem states that this is impossible to achieve. The proof is quite complex, took us two lectures to cover it in CS4231, attached above is a good resource available online that goes over it.

As a thought exercise, try to argue why an algorithm like the one defined below will fail when the initial values are $(0, 0, \dots, 0, 1)$ or $(1, 1, 1, \dots, 1, 0)$ or $(0, 0, \dots, 0, 1, 1, \dots, 1)$ (50% 0s, 50% 1s)

1. Send my own value to every node (including myself)

2. Wait to collect the first $N-1$ values

3. based on a bit-majority / maximum over these values come to a decision

The question that I encountered relaxes the constraints, mainly we are provided with two additional things:

- Each node has a private fair coin that they can flip and generate private random bits. The devil has no control over the randomness, however they can look at these random bits before time.

- We dont need to come to consensus with 100% probability. We just have to maximize our probability and make it a function in $N$, i.e. as $N$ increases our probability of success should tend to $1$. Note: The probability is being taken over the space of all the random bits that will be generated by all nodes. The original binary values that each node has as well as the devils scheduling of messages and failure of a node are all still running in the worst-case scenario, so no leeway there.

Well how will random bits help us? Try to use this hint that the question had associated with it:

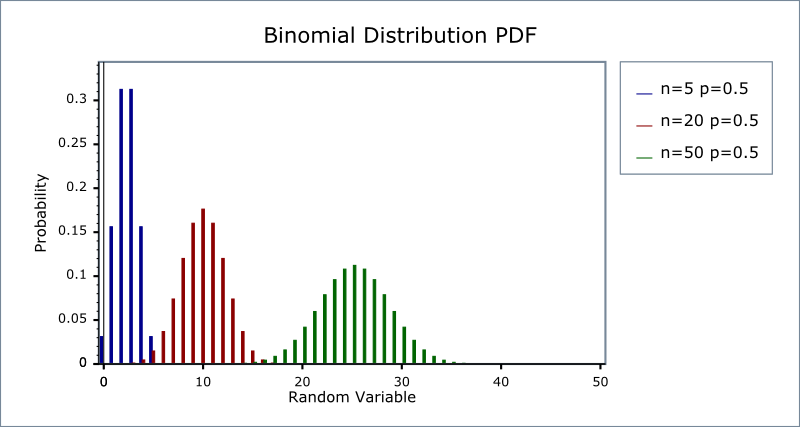

Let $X = X_1 + X_2 + \dots + X_k$ where each $X_i$ is fair coin toss, i.e. 0 if Tails and 1 if Heads. Then $\Pr(X = i) \leq O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{k}}), \forall 0 \leq i \leq N$

Hmm, this sounds like an anti-concentration inequliaty. It is an upper bound of how much probability mass can be present at any point for a Binomial distribution. The proof for the statement above is, $\Pr(X = i) = {k \choose i} \times \frac{1}{2^{i}} \times \frac{1}{2^{k - i}}$ which is maximum when $i = \frac{k}{2}$, when we get $\Pr(X = k/2) = \frac{k!}{(k/2)!(k/2)!} * 2^{-k}$ if we use Stirling’s approximation here, it simplifies this expression to $O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{k}})$.

Try to think of how we can apply this bound and use the private coins to help us out?

Well the idea is pretty straightforward, every node should generate a $0$ or $1$ using the fair coin (let this be $r_i$) and broadcast this (in our message model, the broadcast technically happens one-by-one) to every node (including itself). Once a node (say node $i$) receives $N - 1$ such values, it should take their sum and denote it by $\alpha_{i}$.

Notice, that $|\alpha_{i} - \alpha_{j}| \leq 1, \forall 1 \leq i, j \leq N$. reason being say $\alpha_i$ excluded $r_x$ and $\alpha_j$ excluded $r_y$, in that case, the net delta because of this would be $|\alpha_{i} - \alpha_{j}| = |(\sum_{a = 1}^{n}r_{a} - r_x) - (\sum_{a = 1}^{n}r_{a} - r_y)| = |r_x - r_y| \leq 1$

Tldr; of this entire $\alpha_{i}$’s idea is, that we have come up with an almost random number from $0$ to $N$. I say almost here because the $\alpha_{i}$’s can actually form two values, say one is $Z$ then the other is $Z + 1$, because of the constraint $|\alpha_{i} - \alpha_{j}| \leq 1, \forall 1 \leq i, j \leq N$.

Also notice that the distribution this $Z$ follows, is binomial, since its the sum of $N - 1$ indepdendent bernoullis, so $\Pr(Z = c) = O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N - 1}}) = O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}), \forall 0 \leq c \leq N - 1$ holds.

For the time being, ignore the fact that some nodes came up with $Z$ and some with $Z + 1$ and just think that every node knows the same value $Z$. So now having come up with a consensus on a random number between $0$ and $N - 1$, how does that help us?

Idea 1

Make node $Z$ the leader? And then whatever input value node $Z$ has, everyone follows that value. My natural instinct was to think of this, doesnt work. why? Well, because the devil controls the failure of nodes and can look at the random bits. So the devil can correctly calculate $Z$ and ensure that this node fails, and therefore node $Z$ will just fail before it can tell everyone what its input value is.

Idea 2

Okay, so electing a leader using random bits doesnt work. Lets fall back to the simplest approach of everyone broadcasting their input value ($b_i$), collecting the first $N - 1$ values we see and doing a vote-majority on them. What is vote-majority? We simply say if I receive >= 50% 0s then I will decide on $0$ otherwise $1$.Why does this fail? Because the devil knows that the cutoff is 50% votes, so in the input configuration $(0, 0, \dots, 0, 1, 1, \dots, 1)$ (i.e. 50% 0s, 50% 1s) it can always ensure that atleast two nodes come with contradictory values, one node might see = 50% 0s, but the other might see 49% 0s (because the devil failed one of the nodes which has $b_i$ = 0, mid-way). In that case, former will decide on $0$ and latter on $1$ thus breaking Agreement condition. Now how does having a random variable $Z$ help tweak this algorithm?

What if we tweak the algorithm to: If a node sees more than >= $Z$ 0s then it decides on $0$ otherwise $1$. How does this do?

Well it breaks Validity when all nodes have $b_i = 1$ & $Z = 0$, but this is a extremely low probability event, since $\Pr(Z = 0) = 2^{-N}$. And in the other extreme case, when all nodes have $b_i = 0$, then we are good, since $Z <= N - 1$

What about Agreement? It breaks that too, when one node sees $Z - 1$ 0s, but another sees $Z$ 0s. But this only happens when there are $Z$ 0s and $N - Z$ 1s in the input values. Given a particular configuration say $10%$ 0s and $90%$ 1s, what are the odds that $Z = 10% \times N$, well its at most $O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}})$ because of the upper bound. So we conclude, that for a given configuration the bad case when $Z = \#(b_i == 0)$ is rather low.

But recall that actually some nodes came up with value $Z$ and some with value $Z + 1$, loosely speaking this double the odds of failing (you can work out the exact math on paper-pen). So at an overview:

Pr(Failing) = Pr(No Agreement or No Validity or No Termination) $\leq$ Pr(No Agreement) + Pr(No Validity) + 0 (since this algorithm always terminates)

$ \leq 2 * O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}) + 2 * 2^{-N} \leq O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}})$, for fixed input values configured, over all the random bits generated.

QED.

Note: The exploit of randomization here loosely follows the same idea that this riddle: Two papers uses.

Problem 2

In my final year reseach thesis, we proved a lower bound for 1-bit compressed sensing problem in a very specific setting (publication here, refer to the Technical Overview section to understand the high-leve idea)

I will explain the (n, k)-balanced problem here which reduced to our 1-bit CS problem.

A collection of vectors $V = \{v_1, v_2, \dots, v_m\} \subseteq \{\pm 1\}^{n}$ is (n, k)-balanced if for every subset $S \subseteq \{1, 2, \dots, n\}$ of size $k$ there exists $v_i \in V$, such that $|\sum_{j \in S}v_{i, j}| \leq 1$, i.e. for every given $k$ sized subset of indices, there exists atleast one vector in our collection, whose sum over those index positions is almost $0$

In our research, we were arguing that if each vector in $V$, is constructed by a naive process of coin flipping, i.e. $\forall v_i \in V, \Pr(v_{i, j} = 1) = \Pr(v_{i, j} = -1) = \frac{1}{2}, \forall 1 \leq j \leq n, \forall 1 \leq i \leq n$, then $V$ will fail to satisfy the (n, k)-balanced condition with at-least a constant probility when the size of the collection, i.e. $m = |V|$ is too small.

Note: Here $v_{i, j}$ denotes a rademacher random variable, it is a random variable that is +1 with 50% chance and -1 with 50% chance. Kind of similar to typical bernoulli, just split between $\{-1, 1\}$ instead of the typical $\{0, 1\}$.

Let $F_s$ be the event that for every $v_i \in V, |\sum_{j \in s}v_{i, j}| > 1$, then if $m = |V|$ is too small, we want to show that $\Pr(\bigcup_{s \in \{\pm 1\}^{n}}^{|s| = k}F_s)$ is lower bounded by some constant.

Fact: We used De Caen’s inequality for this (unrelated to the core idea of this blog, but relevant anyways), which states: $\Pr(\bigcup_{i \in I}A_i) \geq \sum_{i \in I}\frac{\Pr(A_i)^2}{\sum_{j \in I}\Pr(A_i \cap A_j)}$, where $\{A_i\}_{i \in I}$ is a finity family of events.

To plug in $F_s$’s for the $A_i$’s in this inequality, we need to calcualte $\Pr(F_s), \forall s$ and $\Pr(F_s \cap F_t), \forall s, t$, where $|s| = |t| = k$. Notice that all $\Pr(F_s)$ will look identical, because of symmetry. Ignore how the intersection event will be calculated precisely (for the purpose of our original problem, this was rather involved and cumbersome).

To understand the anti-concentration inequalities concept better, lets just focus on calculating $\Pr(F_s)$.

Let $E_{s, i}$ denote a single failure event, i.e. $|\sum_{j \in s}v_{i, j}| > 1$, such that $F_s = \bigcap_{i = 1}^{m}E_{s, i}$

To lower bound the the probability of the big bad event $F_s$, we need to lower bound the probability of small bad events, i.e. $E_{s, i}$. Notice that $E_{s, i}$ is basically commenting that the sum of binomial-looking like distribution (which is made up of sum of $k$ independent rademachers) must be away from its center.

We already know that the probability of a binomial being on the center (or any other place) is $\leq O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{k}})$, so the other way around we can say, it will NOT be at the center with at-least probability $\geq 1 - O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{k}})$. This gives us $\Pr(E_{s, i})$

Since all $v_i$’s are indendepent, so $\Pr(F_s) \geq (1 - O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{k}}))^{m}$.

Notice here, if the anti-concentration of binomials had stated that the upper bound is $O(\frac{1}{k})$ (a hypothetical), instead of $O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{k}})$ then our net lower bound result on $\Pr(F_s)$ would have improved (i.e. got higher), thus giving us a tigher lower bound on $m$ (i.e. proof of a larger $m$ not being sufficient for the (n, k)-balanced property to hold).

Takeaways

Anti-concentration inequalities can be useful when you know that in an imaginary world if you could get a uniform distribution, that that would yield you a better result than the distribution you are currently working with.

Think about it, in Problem 1, if we could come up with $Z$ through some construction such that $\Pr(Z = i) = \frac{1}{N}, \forall 1 \leq i \leq N$, then that would be ideal. It would make all the input $b_i$ distributions equally bad for us, each failing with at most $O(\frac{1}{N})$ probability, but in the real world we know that $\Pr(Z = N/2) = O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}})$, so the input distribution of $b_i$ being $(0, 0, \dots, 0, 1, 1, \dots, 1)$ impacts us the most adversely and gives us the fail probability of $O(\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}})$

Similarly in Problem 2, we stated the argument above on how a uniform distribution would have helped us, to further tighten the lower bound on $m = |V|$