Trusting hardness of problems to keep your crpto safe

It’s widely known that 1-way hash functions, particularly SHA-256, are the cornerstone of modern cryptography.

What is a 1-way hash function? A 1-way hash function is a function H(x) where given H(x), finding a corresponding x (even if it’s not unique) is computationally infeasible, requiring brute force on the order of ~2^256 for SHA-256

Even finding a collision, i.e. two values $a \neq b$ such that $H(a) = H(b)$ takes ~2^128 attempts due to Birthday Paradox.

In this post, we’ll explore the usage of 1-way hash functions in DeFi (Decentralized Finance) where their significance becomes immediately clear, without being obscured under layers of abstraction.

The two use-cases we will be exploring are:

- Atomic Swaps (useful)

- Bitcoin Puzzles (causes climate change, has front-runners, but still cool)

Another popular use case of 1-way hash functions is Merkle Trees, since there are tons of resources online covering this, so I won’t cover it.

Bitcoin Opcode1 - A Primer

Many assume Bitcoin is just a “decentralized Venmo” —a simple ledger with no smart contract functionality. But Bitcoin does have programmability through its script system, a stack-based language that dictates how funds can be spent. While not as expressive as Ethereum’s Turing-complete contracts, Bitcoin Script is still powerful enough to showcase the utility of 1-way hash functions.

Bitcoin blockchain is a ledger of unspent money. We’ll simplify by considering transactions with a single input and single output.

A bitcoin transaction (simplified) consists of:

- Parent transaction ID: ID of the transaction whose money is being spent

- Amount: Amount of BTC being transferred

- ScriptSig: Unlocking script attached to the parent transaction

- ScriptPK: Locking script attached to the current transaction

- Mining fees: Fees paid to miners for including this transaction in the blockchain

where a transaction is considered valid2 iff the program ScriptSig | ScriptPK evaluates to true and there is no double-spend (i.e. the same parent transaction is not being spent by two transactions) 3

Note: The ScriptSig here refers to the ScriptSig of the current transaction whereas the ScriptPK refers to the ScriptPK from the parent transaction whose money is being spent.

We simplify the blockchain as a chain of valid transactions that > 50% miners agree upon, ordered chronologically.

Let’s take a basic example to ramp-up:

Alice wants to send Bob 5 BTC

- Bob generates a random secret key (also called private key): $sk_B$

- Bob computes his public key: $pk_B = sk_B \times G_{secp256k1}$ where $G_{secp256k1}$ is a constant under the cryptographic modulo field

- Bob computes his wallet address as address$_B$ = SHA256($pk_B$). In reality, address$_B$ = OP_HASH160($pk_B$) = RIPEMD160(SHA256($pk_B$)) but for the sake of simplicity we will assume that this is SHA256($pk_B$)4

-

Alice posts the transaction X on Bitcoin blockchain

Tx ID Parent Tx ID Amount ScriptSig ScriptPK Mining Fees X $\small{\text{Alice’s Old Tx}}$ 5.2 <Ignore> ScriptPK 0.1 Where ScriptPK:

OP_DUP OP_SHA256 address_B OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIGThe entire transaction is signed by Alice and that sign is also added at the end of transaction, so any specific miner attempting to change ScriptPK would invalidate Alice’s signature, thereby invalidating the transaction.

-

To spend the money, Bob must construct a new transaction (namely Y) with a valid unlocking script (ScriptSig) that, when concatenated with the locking script (ScriptPK), evaluates to true.

Tx ID Parent TxID Amount ScriptSig ScriptPK Mining Fees Y X 5.1 ScripSig <Ignore> 0.1 Where ScriptSig:

SIGN(sk_B, Y) pk_B -

Miners would validate this ScriptSig | ScriptPK (concatenated script) to check if this transaction Y is valid or not. i.e:

SIGN(sk_B, Y) pk_B OP_DUP OP_SHA256 address_B OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

Bitcoin Opcode is run in a stack based manner, so as we run the script, we would see the following stack:

- Bob provided unlocking script portion is run first:

- First push in SIGN($sk_B$, Y)

- Then we push in $pk_B$

- Then the locking script portion is run:

- Then OP_DUP triggers duplication of the top element, i.e. $pk_B$ is pushed again

- Then OP_SHA256 hashes (with SHA256) the top element of the stack

Stack now:[SIGN(sk_B, Y), pk_B, SHA256(pk_B)] - Then we push address_B ( = SHA256($pk_B$)) onto the stack

Stack now:[SIGN(sk_B, Y), pk_B, SHA256(pk_B), SHA256(pk_B)] - OP_EQUALVERIFY checks it the top two elements of the stack are equal or not, if not returns false immediately, otherwise pops the top two elements

Stack now:[SIGN(sk_B, Y), pk_B] - OP_CHECKSIG verifies if the signature = second element of stack, using the public key = top stack element, is a valid signature for the transaction. Formally speaking it checks if

VERIFIER(SIGN, pk_B, SHA256(Tx)) == 1?, whereVERIFIERis a function that checks if the signature is valid or not.

This setup of ScriptSig|ScriptPK is called Pay-to-Public-Key-Hash (P2PKH)

You should think carefully on how no one apart from Bob could submit a valid ScriptSig in a transaction to steal this money.

Specifically think of why Bob is not afraid of some miner in between that would see SIGN($sk_B$, Y) and $pk_B$ and then attempt to post a transaction faster than Bob which uses these two in their ScriptSig This is a failed attempt of a front-run attack, where a miner sees a pending transaction and tries to submit a competing one with a higher fee so it gets included first and the original one is subsequently rejected since it tries to do a double-spend.

Spoilers: Notice the two cryptographic primitives in play here: SHA256 + OP_EQUALVERIFY and SIGN + OP_CHECKSIG.

- In the first transaction (i.e. X), only the address_B = SHA256(pk_$B$) is revealed, which is a one-way hash function, so no one can reverse engineer the public key from this, therefore Bob is not worried that someone will pass the OP_EQUALVERIFY check of the first script, at-least not before they reveal the public key.

- And the SIGN($sk_B$, Y) is a signature that is unique to this transaction, so even if someone has $pk_B$ and tries to front-run Bob, they would not be able to sign their transaction wth $sk_B$ (which would look different from Y, so they can’t re-use this signature) and hence the OP_CHECKSIG would fail.

Atomic Swaps

Alice wants to swap 5 BTC for Bob’s 10 ETH without any intermediary. Bitcoin and Ethereum are two different blockchains, so this not supported out of the box.

Also note that the two blockchains are public so everone can see the metadata of all the transactions (i.e. the amount, wallet addresses, programming opcodes, etc)

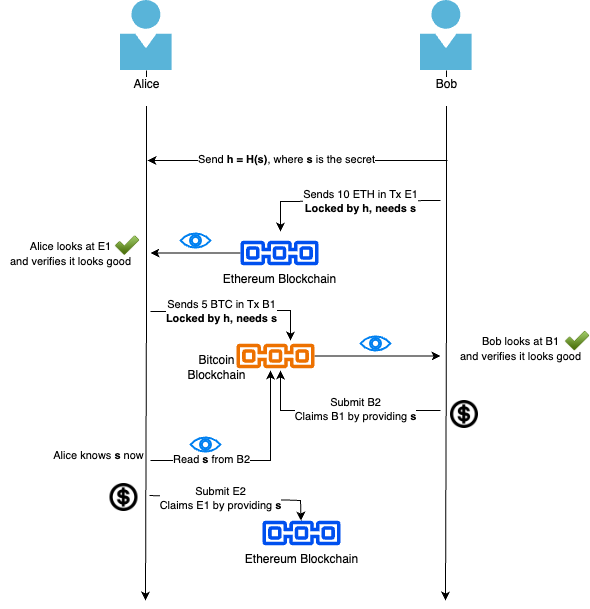

The core idea is that on an off-channel, Bob broadscasts the hash($h$) of a secret($s$). and creates a transaction X on Ethereum blockchain that sends 10 ETH to Alice which can be claimed only when Alice provides the secret $s$ such that $h = \text{SHA256}(s)$. Alice does the same, creating a transaction X on Bitcoin blockchain that sends 5 BTC to Bob’s wallet if Bob provides the secret $s$ such that $h = \text{SHA256}(s)$.

- The Easy Case: When Bob claims the 5 BTC from Alice, he reveals the secret $s$ publically on the bitcoin chain, Alice observes this $s$ and can now use it to claim the 10 ETH. Both the transactions are constrainted to corresponding wallets, so no one else can claim the money.

-

The Hard Case: If one party tries to back out or tries to intentionally cheat the other party. Firslty, notice that there is a slight asymmetry here, Bob is the one who has the secret and it seems like he holds more power, but this is not the case because of these two reasons:

-

Order of transaction creation: Bob’s transaction should be published before Alice’s transaction, so that Alice can see the locked ETH claim-able by Alice upon providing a $s’$ such that SHA256($s’$) = $h$ before she publishes her transaction. Alice needs to be aware that Bob can claim her monday instataneously when she publishes, so she needs to be sure that she can claim the 10 ETH immediately after Bob claims the 5 BTC.

-

Time-locking: Obviously, Bob will be the one to claim their BTC first since they have the secret, but what if they don’t claim? We don’t want Alice’s BTC to be stuck in that transaction, so we add a way for Alice to re-claim the 5 BTC back if Bob does not claim it within a certain period. This is called a time-lock (think of it as a time-bomb). Similar time-locking was also done by Bob in his script published in the Ethereum blockchain…try to think of why? what would he be afraid of?

Spoiler: Bob is afraid that Alice might never create the transaction on Bitcoin blockchain or creates an invalid one (say instead of using $h$ she uses $h’$ or a different wallet address to send the BTC to). So Bob adds a time-lock to his transaction too, so that they can re-claim the 10 ETH after a certain period of time, if they are suspicious of Alice’s transaction being invalid or if Alice never creates the transaction.

The script for Alice’s locked 5 BTC on Bitcoin blockchain would look like:

OP_IF # Bob can claim BTC if he reveals the secret preimage OP_SHA256 <hash_of_secret> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <Bob's_PubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_ELSE # Alice refunds BTC if Bob never reveals the secret <locktime_Alice> OP_CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY OP_DROP OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <Alice's_PubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_ENDIF OP_CHECKSIGSimilar script would be created by Bob on the Ethereum blockchain. Note: Technically, Ethereum uses Solidity which is even more expressive, but the idea remains the same.

-

We have shown a way where two individuals who do NOT trust each other are able to exchange funds across blockchains (atomically) without trusting any central authority or intermediary.

Food for thought: Say Bob in his transaction makes a time-lock of 5 days, should Alice also make a time-lock of 5 days in her transaction, should it be more or less? Why?

Bitcoin Puzzles

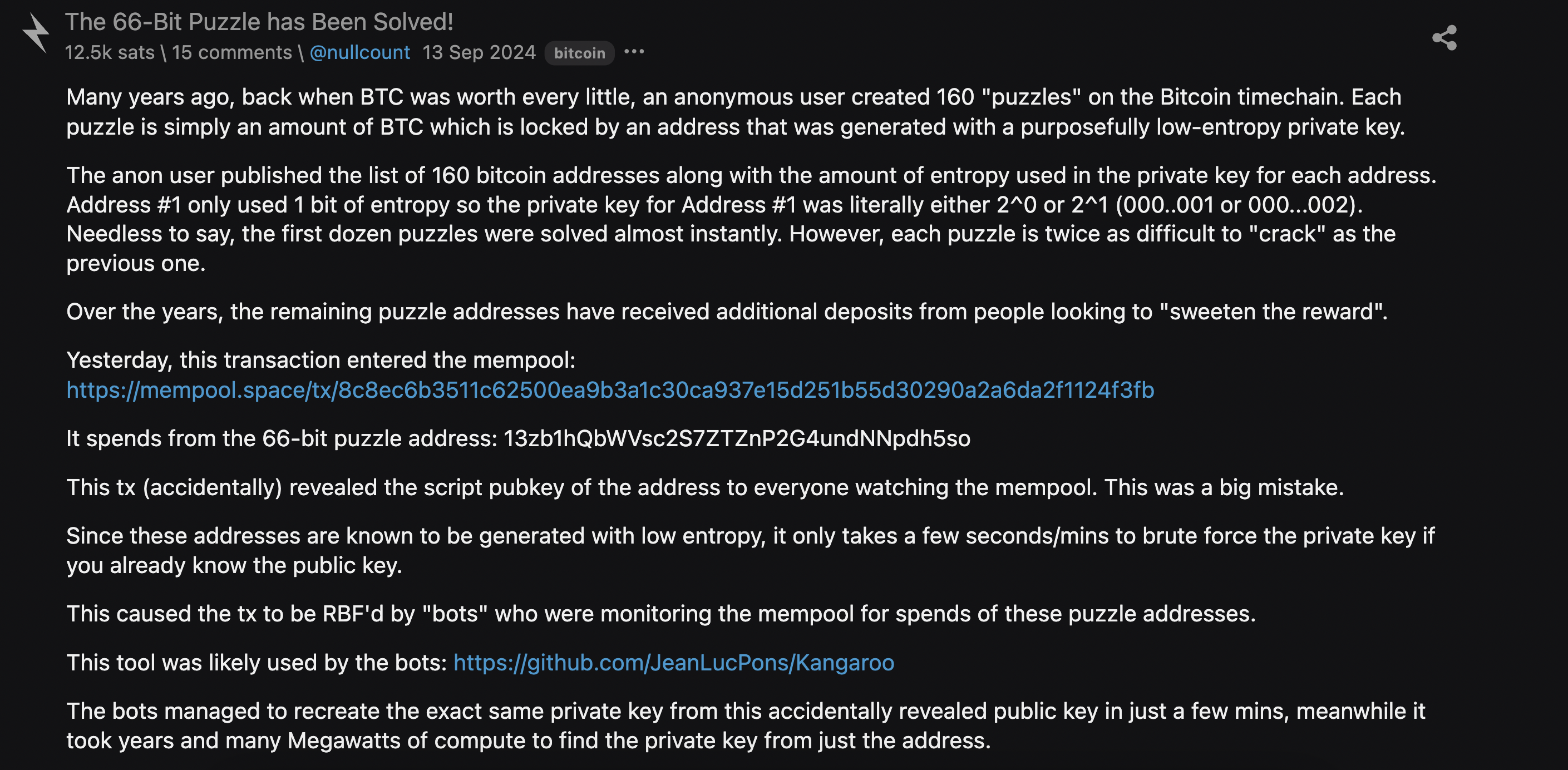

This post perfectly explains the hype around Bitcoin puzzles. Attaching the screenshot below:

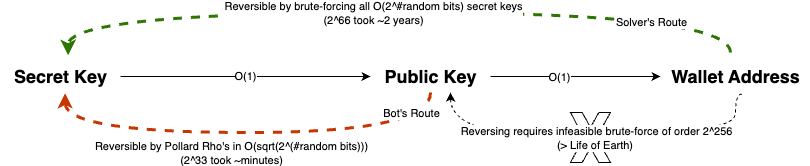

The Bitcoin 66-bit puzzle was a cryptographic challenge, where instead of a full 256-bit secret key generated randomly, the puzzle’s secret key has only 66 bits of randomness. This drastically reduced the search space to $2^{66}$ - still massive, but feasible if you have the resources. After ~2 years of compute, a solver having brute-forced each of the candidate $2^{66}$ secret keys, generating the corresponding public key and then checking if the SHA256(public key) = the wallet address used in the puzzle, eventually found the correct secret key. To claim the 6.6BTC (present value ~100k USD), they submitted a transaction with public key (NOT the secret key) and the corresponding signature (using the found secret key) (Recall the P2PKH setup we explained above). The transaction also had some fees attached for the miners to include it in the blockchain.

Allegedly, someone had a live bot looking for the puzzle-solving unconfirmed transaction in the miner pool, which once they saw, they knew the public key, now they still had to figure out the secret key. But here comes the punchline, figuring out a low entropy5 secret key from the public key is actually much simpler using Pollard’s rho algorithm which takes time O(sqrt(n)) where n is the size of the group, in this case $\sqrt{2^{66}} \sim 2^{33}$, which suddenly becomes crackable in minutes. This bot once having cracked this secret key, posted a similar transaction as the original solver but with a higher fee, so that it gets confirmed faster and effectively drained the 6.6BTC from the puzzle wallet to their own faster than the original solver could.

Is the moral here to tip your miners well? Well… you should if you are making ~100K but the actual crux is that the puzzle was originally hard because the presence of the 1-way hash function made it hard to reverse engineer to the low entropy secret key, but once we removed the 1-way’ness by revealing the public key, the problem became much simpler.

Great sources to read more about this puzzle, other related attacks and concerns: Hacker News, Should your public keys be private, Dark Skippy Attack

Food for thought: Can this idea of “claim money for solving hard puzzles” be used to incentivize people to spend their compute + intellectual skills to solve real-world compute problems?

Most of the concepts presented here have been taken from the course CS251 - Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain Technologies

-

2: Valid here means, miners accept it. Obviously miners can be adversarial, but we assume always that > 50% of the miners will work truthfully, if they don’t then yes the system might break. ↩

-

3: There are other conditions too, but we will skip them as they are irrelevant to our discussion ↩

-

4: Bitcoin passes the public key through two hash functions to get the wallet address as an additional security measure, and also to make the wallet address shorter (since output domain of RIPEMD160 is just 160 bits, whereas SHA256 is 256 bits). For our discussion we assume the absence of RIPMED160 and consider the wallet address as just the SHA256 of the public key. ↩

-

5: Entropy is a measure of randomness, the more random a secret key is, the harder it is to guess. Low entropy here means that the secret key was not very random, so the search space was smaller and subsequently the group in which Pollar’s rho algorithm was working was smaller. ↩