If you think “hashing is just for lookups”, then this post is your red pill.

This two-part series explores how hashing is used beyond hashmaps - in settings where randomness and probabilistic reasoning are the real heroes.

In this first part, we will see 2 examples where hashing is used to simulate uniformity, even when the input is highly structured or biased and helps in estimating the cardinality of sets (even when we can’t list them explicitly)

-

LogLog: Here we are given a huge stream of numbers (think in the order of billions if not more), and we want to estimate the number of unique numbers in this stream (i.e. the cardinality of this set). The catch? You can’t store all the unique numbers in memory (assume big-data, so you don’t have this much memory), so any typical leetcode solution of storing these in a hashmap or a binary search tree won’t work. This is a very practical problem, popularly encountered in Redis1 (Example: keeping track of unique IPs visiting a website)

-

#SAT (ApproxMC): The well-known SAT problem looks as follows: given a boolean formula which is a AND of ORs (see $\phi(\overrightarrow{x})$ below), is there a way to assign values to the variables such that the formula evaluates to true? The problem is the most classical NP-Complete problem. Here, we’ll discuss #SAT, i.e. counting the number of such satisfying assignments. Obviously this problem as it is, is quite hard (#P-Complete), but we will see how with a black-box (i.e. a SAT + XOR solver), we can estimate the number of satisfying assignments.

Solutions for $\phi(\overrightarrow{x})$ are: \(x_1 = 0, x_2 = 0, x_3 = 1\\ x_1 = 1, x_2 = 1, x_3 = 0\\ x_1 = 1, x_2 = 1, x_3 = 1\\\)

I recommend spending ~15 minutes trying to come up with some solution ideas yourself to fully appreciate the novelty of the approaches we’ll explore.

Note: Discussions on LogLog is common in Randomized Algorithms courses. As for #SAT, I encountered it in a Computational Complexity class.

Table of Contents

LogLog

LogLog algorithm (also called Flajolet Martin) and its improved cousin HyperLogLog, estimate the cardinality of a set, using very little space (i.e. O(log log n) bits, where n is the cardinality of the set).

Suppose we have a hash function $H$ which maps2 each element of the stream to a uniform bitstring. Say H(35) = 10011100100, then we say the number of trailing zeros in the hash value of 35 is 2. The number of trailing zeros is simply the count of 0s from the right-most bit to the first 1 bit.

If you hash each item to a uniformly random bitstring, the probability it starts with $k$ zeros is $1/2^k$.

The core statistic we will use is: R = max number of trailing zeros in the hash values of the elements in the set, and our estimate will be $n’ = 2^R$

Intuition of why this could work

-

Expected number of items starting with $k$ zeros is $n/2^k$, so if we see $2^{10}$ unique items, then on average we would expect ~1 item starting with 10 trailing zeros. Inversing this argument, if we see 1 item with 10 trailing zeros, then we can estimate that the number of unique items is $2^{10} = 1024$.

-

Say, we only see, say 4-5 distinct elements in the stream, for example: its a DNA string with only A/G/C/T, then it’s very likely that all the 4 values, hash to bitstrings with few number of trailing zeros.

Example: H(A) = 1101010, H(G) = 0001010, H(C) = 1001001, H(T) = 0011100, here the maximum number of trailing zeros is 2 (i.e. $R = 2$), so we would estimate the cardinality to be $2^R = 4$

- If we see a million unique elements in our stream, then there is a good enough chance that some elements will hash to bitstrings with a large number of trailing zeros like: H(x) = 1010110…00

Quick Question: If you see 1 million unique elements in your stream, what do you think the value of $R$ (i.e., the max number of trailing zeros) would be?

Hint: If the probability of seeing a hash with $k$ trailing 0s is $\frac{1}{2^k}$, and you’ve seen 1 million items, what’s the largest $k$ for which you’d expect at least one such hash?

Thought Experiment

Say you have a stream of n distinct IP addresses (obviously, some appearing more than once), and you hash each of them to a uniform random bitstring. Then you do the staircase3 experiment, i.e. each IP address hashes to a ball which falls down the staircase to the step where its hash value has the number of trailing zeros equal to the step number. Now you observe that at step 7 there is 1 ball, and there are no balls on subsequent steps. What would you guess the original number of unique balls there were at the start of this experiment at the top of the staircase? (Hint: Each step ~halves the number of balls)

Playground (LogLog)

Specify stream size and distinct elements:

Or enter a comma-separated list of numbers:

R (Maximum number of trailing zeros):

Estimated Cardinality:

The staircase animation below is built with D3.js — crude for now. PRs welcome if you’re D3-savvy!

Notice, we never stored the full stream in this algorithm. Neither did we store the hash values of the elements. We only hashed each element as it came, maintained a single integer $R$ (which is the maximum number of trailing zeros we have seen so far), and then at the end estimated the cardinality as $2^R$. With a single integer R (which can range from 0 to log(n), thus taking O(log log n) bits), we were able to do our estimate.

HyperLogLog extension idea

HyperLogLog just builds up on LogLog, by dividing the stream into buckets using some prefix of the hash value, say first two bits of the hash value decide the bucket id (in 0 to 3) and then in each bucket, we keep track of a local $R_i$ (i.e. the maximum number of trailing zeros), then for each bucket we get the estimate $n’_i = 2^{R_i}$, and finally we combine these estimates (interestingly enough, harmonic mean is the best way to lower the variance) to get the final estimate4.

Note: I skip the math analysis portion, as I think the intuition is good enough to understand the core idea of this algorithm. If you are interested in the math, I would recommend looking at the NUS Lecture Notes and other readings5

Why was hashing helpful here?

The hash function along with the statistic of “maximum number of trailing zeros” gave us a way to measure a rare event on the set of unique elements of the stream. Our intuition was that if the rare event happens then that implies there is a large number of unique elements in the stream.

Take a toy example: Say we have some hash function, which hashes our numbers to the range $[0, 1]$ uniformly, and we have a way to define the rare event as: Is there a hash value in our stream which lies in the range $[0.2, 0.3]$. Now crudely speaking, if you hash say only 5 unique elements, do you think this rare event will mostly be true? (Answer: Not really, with probability $0.9^{5} \sim 0.6$, this event won’t happen)

But what if we hash ~30 unique elements, do you then think this rare event will mostly be true (Answer: Most likely yes, with probability $1 - 0.9^{30} \sim 0.95$, this event will happen)

Note: Sure, a 0.6 and 0.95 distinction may not seem overwhelming — but even modest gaps let us amplify confidence through repetition. Till the time these are better than 50-50 chance, we can simply run the experiment multiple times and take the majority vote result. Some math can show that you only need to run such an experiment a few times to become super-confident (say 99%) about the result.

Testing against a rare event (it could be trailing number of zeros or defining some other sort of “subset” of the hash values) and then reverse-engineering the estimated number of unique samples based on the result of the test is a common theme when we use hashing to randomize our input space.

Playground (Core Idea)

Add some input points in the “input space” on the left side and draw a rare event region in the “hashed space” on the right side. Then run, “Hash & Test”, which will hash the input points to the “hashed space”, and if any of them lie in the region, we say the rare event happened. Based on this test, we can infer if the number of points in the input space is large or small.

Input Points

Rare Event Region

Once you click “Hash & Test”, you can drag and resize the polygon to see how the rare event region changing affects the results.

Percentage area of rare region (p):

Rare region is hit:

Inference:

#SAT (ApproxMC)

The #SAT problem is a counting problem, where we are given a boolean formula in CNF (Conjunctive Normal Form - AND of ORs) and we want to count the number of satisfying assignments. We assume to have a SAT+XOR solver6 which given a formula can tell yes/no if it is satisfiable

Note: Even with this assumption, it is highly non-trivial to count the number of satisfying assignments. Be my guest if you want to try this exercise out.

The Approach

We solve the simpler problem, call it “#SAT $> 64S$ or $< S$”, where we are given a formula and want to know if the number of satisfying assignments is $> 64S$ or $< S$. If we could solve this, then we could simply binary search on $S$ and end up with knowing in which bucket of $[S, 64S]$ the number of satisfying assignments lies (i.e. get an approximate count).

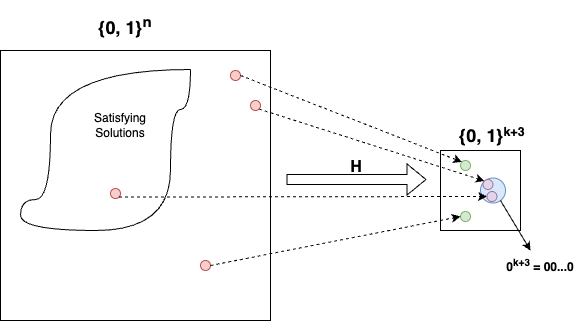

For this simpler problem, we define a hash function $H$ that takes in every possible assignment of the variables and hashes it to a uniform bitstring of size $k$

\(H: \{0, 1\}^n \to \{0, 1\}^{k + 3}\) 7

For instance: $H(x_1 = 0, x_2 = 1, x_3 = 1, \dots, x_n = 1) = 11010, H(x_1 = 1, x_2 = 0, x_3 = 1, \dots, x_n = 0) = 00100$

Also assume that this hash function can be constructed as an AND of XORs of the variables

Toy example: $H(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)_0 = x_1 \oplus x_3 \oplus x_n, H(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)_1 = x_2 \oplus \neg x_4 \oplus x_n$ (0th and 1st output bit dummy compute)

Now, comes the core idea:

We will use the hash function to define a rare event, i.e. if there exists an assignment $\overrightarrow{x} = (x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)$ such that $\phi(\overrightarrow{x}) = 1 \land H(\overrightarrow{x}) = 0^{k + 3}$, then with high probability number of satisfying assignments is $> 64S$, and $< S$ otherwise.

Here, we will use our SAT+XOR black-box solver to get the answer to the yes/no satisfiability question for $\phi(\overrightarrow{x}) = 1 \land H(\overrightarrow{x}) = 0^k$

$0^{k + 3}$ is the all-zero bitstring of size $k + 3$, and is in no way special. It is just used to define a rare event. The idea same as before, is that if the number of satisfying assignments is large, then there is a good chance that some of them will hash to $0^{k + 3}$ (i.e. the rare event will happen).

Note: Let the number of satisfying assignments be $P$, and after hashing all those assignments fall into random $2^{k + 3}$ buckets, then in expectation one would see $P/2^{k + 3}$ satisfying assignments in the $0^{k + 3}$ bucket. We have the relationship between $S$ and $k$, that $S = 2^{k}$, so that this number $\frac{P}{2^{k + 3}} = \frac{P}{8S}$. Testing if this is $\geq 1$ or not, helps us predict if $P$ is $> 64S$ or $< S$, this testing idea is analgous to the Playground (Core Idea) section above.

By some math8, we can show that with probability $\geq 3/4$, this algorithm correctly determines if the number of satisfying assignments is $> 64S$ or $< S$. We can repeat this experiment multiple times to get a better confidence level, and subsequently binary search on $S$ to get a better estimate of the number of satisfying assignments.

Conclusion

In this post, we saw that the uniformity property of hashing buys you so much more than just an efficient lookup table. We can use it to define rare events, and then use these rare events to estimate the cardinality of sets (be it number of unique elements in a stream or the number of satisfying assignments).

You can find this idea in other places also, say Bitcoin mining, where the miners try random inputs (nonce values) on the block they are mining to produce a hash (double SHA-256) of the block which meets certain criteria (aka a rare event definition). This rare event is defined as: the hash needs to have a certain number of leading zeros in hexadecimal. The difficulty of hitting this rare event controls the speed of mining and drives the proof of work principal of the protocol.

In part two, we will look at settings where hashing isn’t just random chaos - but actually encodes some properties of the object being hashed. Most commonly used in Locality Sensitive Hashing, to solve problems like nearest neighbor, etc.

-

2: Such a hash function might sound magical, but is not. Murmurhash3 which takes in a seed is considered a good enough uniform hash function for our purpose. ↩

-

3: Prof Seth Gilbert from NUS uses this staircase analogy in his notes ↩

-

4: HyperLogLog multiplies this final estimate with a multiplicate bias $\alpha_M$, which depends on the size of the stream. This is a correction factor to account for the inherent collisions in the hash functions. ↩

-

5: HyperLogLog in Meta - Good intuition of aggregation step of HyperLogLog ↩

-

6: CryptoMiniSat SAT Solver is one such popular SAT solver (with the XOR extension) ↩

-

7: The precise math, requires $k$ to be $k + 3$ (A nuisance for the math to work out) ↩

-

8: Credits to Prof. Li-Yang Tan who teaches CS254 at Stanford. Attaching his lecture notes here, which cover the math as well as how to construct the required hash function ↩