Proving that something exists, but being too lazy to find it.

I am currently taking a course on “Discrete Probabilistic Methods” where we deal with problems of the form: Prove some object X exists with Y properties?

Proving the existence of an object with certain properties is often much simpler than actually constructing or finding that object. The tools we use to make these concrete, deterministic claims, are ironically based on probability. Thus, the technique is called Probabilistic Methods. It can be applied to a variety of problems in graph theory, set theory, and coloring, etc and requires at-most an undergrad-level exposure to probability.

In this post, I’ll discuss two fascinating (and quite distinct) problems I encountered during the first few weeks that showcase the power of these methods. My hope is that by the end of this post, you will be convinced that this is a pretty magical area of math. To fully appreciate the elegance of these proofs, I strongly suggest spending a decent amount of time $\text{[30 minutes, 2 days]}$ tackling these problems with just the knowledge you already have. Only once you realize that classical discrete math ideas don’t work here or are too cumbersome, can you fully appreciate the concepts we present later.

Problems

Q1. $\text{[Medium]}$ Given a graph $G$, where $M$ denotes the number of pairs of edges that do NOT share a vertex. Show that there exists a way to draw this graph on a 2D plane (say a sheet of paper), where the number of “crossings” (a crossing is when two edges intersect on the 2D plane) is $\leq M/3$.

[You might ask: Who cares about this problem? Well, imagine asking an intern on your team to draw a graph for a PowerPoint slide, only to find it looks cluttered with too many crossings. At least now you can berate them, empowered with the knowledge that there “exists” a better way to draw the graph, though you might not know it — jokes aside, I agree that some of these problems can feel a bit out there on the edge of relevance!]

Q2. $\text{[Hard]}$ Given a set of positive integers $A$ of size $N$, show that there always exists a subset $B \subseteq A$, of size $\geq N/3$ such that:

\[\forall b_1, b_2, b_3 \in B, b_1 + b_2 \neq b_3\]i.e. for all triplets in $B$, sum of two elements does not equal to the third element

Our Toolkit

Now lets cover a couple of basic things in probability theory which will be required in our proofs:

- For a random variable $X$, $E[X]$ denotes its expected value. Simply put it’s the average value of $X$.

Example: Say $X$ is the outcome of a dice roll. Then $E[X] = \frac{1+2+3+4+5+6}{6} = 3.5$

- $U(0, 1)$ denotes a uniform distribution over the range $(0, 1)$. This means that any value in this range is equally likely to be picked.

Example: Say $Y \sim U(0, 1)$. Then \(E[Y] = \int_{0}^{1}xdx = 0.5\) and \(Pr(Y \in (0.1, 0.8)) = 0.7\)

-

If you have two random variables $X$ and $Y$, then $E[X + Y] = E[X] + E[Y]$ This holds irrespective of whether $X$ and $Y$ are related to one another1 – famously known as Linearity of Expectation

-

Lastly if $E[X] = c$, where $c$ is a constant, then from the sample space from which $X$ is drawn, there must exist some value $x \leq c$ and some value $x \geq c$ This might sound a bit mathy or complex, but it’s really saying something simple. Suppose you are in a room of 100 people, and you calculate the average amount of money each person has in their pocket is 30\$. Then, there must be at least one person in this room who has $\geq 30$\$, and at least one person who has $\leq 30$\$.

That’s it. You have all the tools necessary for the job. Let’s dig in:

Solutions

Q1. Given a graph $G$, where $M$ denotes the number of pairs of edges that do NOT share a vertex. Show that there exists a way to draw this graph on a 2D plane (say a sheet of paper), where the number of “crossings” (a crossing is when two edges intersect on the 2D plane) is $\leq M/3$.

Hmmm…your first thoughts might be, how am I supposed to get this $/3$ constant in my calculation and how do I try all types of ways to draw $G$ (sounds pretty impractical)

Fair questions. Say we enumerate all the $M$ pairs of edges that don’t share a vertex as $F_1, F_2, F_3, \dots, F_M$.

And make $M$ new random variables $X_1, X_2, \dots, X_M$, are defined as follows:

\[X_i = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } F_i \text{ is a crossing in our drawing} \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]Such an $X_i$ which can only take $0/1$ values is commonly called an indicator random variable (and is often useful)

Then our total number of crossings will be:

\[X = X_1 + X_2 + \dots + X_M = \sum_{i = 1}^{M}X_i\]If we can show that each $E[X_i] \leq 1/3$ (we will come to this later), then:

\[\begin{align*} \text{Given }E[X_i] &\leq \frac{1}{3}, \forall i \in [1, M]\\ E[X] &= E[X_1 + X_2 + \dots + X_M]\\ &= E[X_1] + E[X_2] + \dots + E[X_M] \text{ [Using Linearity of Expectation]}\\ &\leq \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{3} + \dots + \frac{1}{3}\\ &= \frac{M}{3}\\ \Rightarrow E[X] &\leq \frac{M}{3} \end{align*}\]Convince yourself that showing $E[X] \leq M/3$ is enough to show that there is a drawing with $\leq M/3$ crossings. With the caveat that we haven’t yet defined what random process we are using to draw these graphs and subsequently over what probability space is this “expectation” being taken over.

We also know a very trivial fact:

\[\begin{align*} E[X_i] &= Pr(X_i = 1)\times1 + Pr(X_i = 0)\times0\\ &= Pr(X_i = 1)\\ &= Pr(\text{a specific pair of edges cross in our drawing of G}) \end{align*}\]Showing $E[X_i] \leq 1/3$ reduces to showing that the probability a specific pair of edges will cross in our drawing is $\leq 1/3$.

At first glance this decomposition of the problem might not seem helpful - after all, crossings depend on multiple pairs of edges. However, linearity of expectation allows us to analyse each pair independently, without worrying about how this pair of edges interacts with the others.

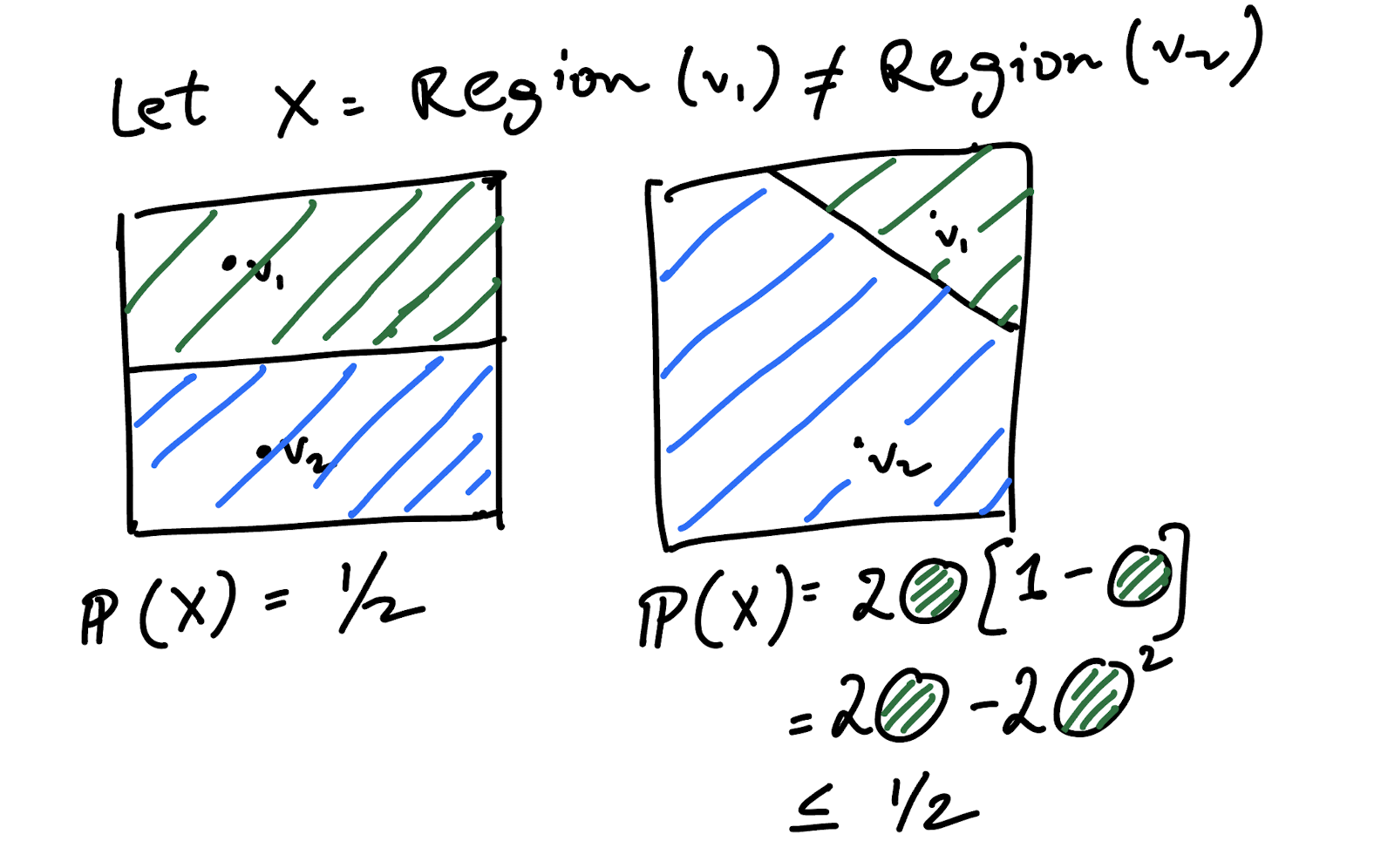

This sketch is a good starting point for your thought process on thinking what kind of random process would be used to draw this graph. If one edge cuts the entire plane into two half-planes and you place the other two vertices at random, then there is at most a $\leq 1/2$ chance that they end up on opposite sides, thereby crossing the first edge.

Issues? Our naive bound right now is $1/2$ (but we want $\leq 1/3$) AND the more glaring issue…you want a randomized process to put all the vertices of the graph on the plane not just two vertices.

Another hint here would be: Think of a way to put all the vertices, such that all of them are symmetric in some sense? Reason: We know that the claim is supposed to hold for all graph $G$’s and not just a specific one, so its likely that the drawing process is symmetric and ignorant of the way edges are connected within a graph.

…

Spoiler

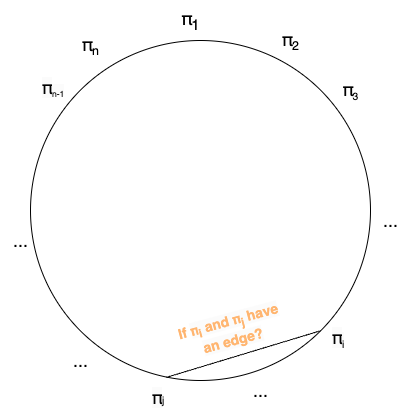

Put all the points on a ring as a “random permutation” and then draw the edges.

Quick check: How many permutations of N nodes can you put on this ring? Answer: $(N - 1)!$ (if you consider the cyclic shift of a permutation as the same permutation)

That’s it…let’s now analyze Pr(a specific pair of edges cross) using this arrangement^

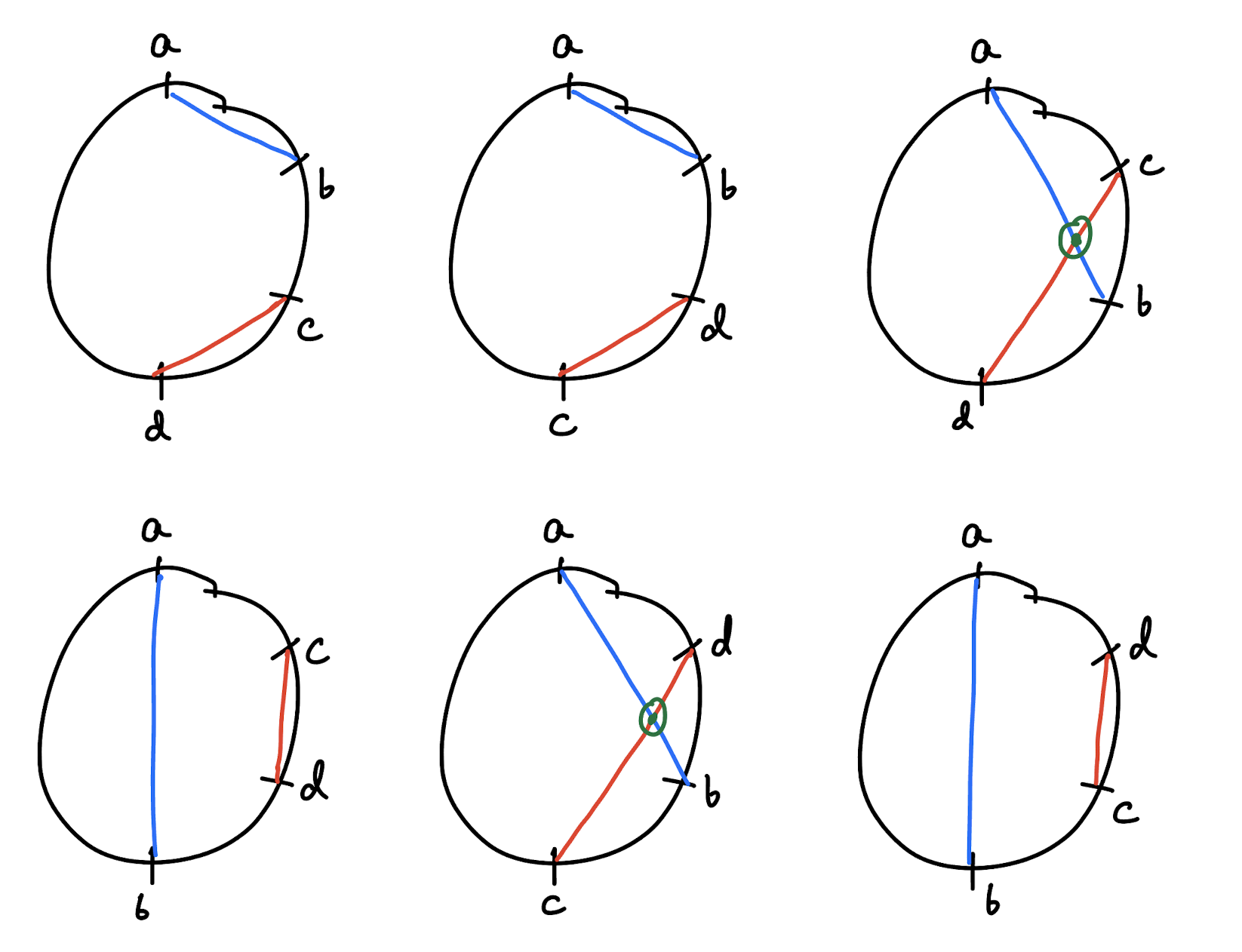

Let the end-points of the first edge be denoted by $(a, b)$ and the end-points of the second edge be denoted by $(c, d)$. Since they do not share a vertex, so you know $a, b, c, d$ are all distinct.

Then in which all scenarios would they cross and not cross? (Without loss of generality, assume $a$ is the first node in the clockwise order)

- … a … c … b … d … OR

- … a … d … b … c …

^They cross

- … a … b … c … d … OR

- … a … b … d … c … OR

- … a … c … d … b … OR

- … a … d … c … b

^They don’t cross

So in $2$ out of the $6$ ways to orient (a, b, c, d) on a circle do the two edges intersect, i.e. a chance of $2/6 = 1/3$. Ta-da!!

Food for thought: Design an algorithm that, for any given graph $G$, finds a 2D-drawing with $\leq 2M/5$ crossings. Sometimes proving existence hints you at ways to even find THE object or a slightly weaker version of it.

Q2. $\text{[Hard]}$ Given a set of positive integers $A$ of size $N$, show that there always exists a subset $B \subseteq A$, of size $\geq N/3$ such that: \(\forall b_1, b_2, b_3 \in B, b_1 + b_2 \neq b_3\)

i.e. for all triplets in $B$, sum of two elements does not equal to the third element

This question at first glance is super intimidating and to be honest it would be nothing short of amazing if a person can come up with the proof from scratch2.

Hint 1: The set of reals $(1/3, 2/3)$ (i.e. all the real numbers in the range 0.3333… to 0.66666…) follows the property that for all $3$ element tuples from this set: $b_1 + b_2 \neq b_3$3

Hint 2: Come up with a function $f$ which transforms each positive integer in $A$ to a real in $(0, 1)$, such that: $ f(A_i) \sim U(0, 1) \Rightarrow Pr(f(A_i) \in (1/3, 2/3)) = 1/3$. Do note here the set $A$ is already built so there is no randomness in the set $A$ itself, but the randomness comes from the function $f$.

…

Let f be: $ f(a) = \text{frac}(a\theta) = a\theta - \lfloor a\theta \rfloor, \theta \sim U(0, 1)$

(Example: $f(3.14) = 3.14 - \lfloor 3.14 \rfloor = 0.14$)

Where we sample \(\theta \sim U(0, 1) \Rightarrow \text{frac}(a\theta) \sim U(0, 1)\)

Spolier of why $\theta \sim U(0, 1) \Rightarrow \text{frac}(a\theta) \sim U(0, 1)$

Can think of $\text{frac}(a\theta) = a\theta \text{ mod } 1$. Since $\theta \sim U(0, 1)$, multiplying it by $a$ (think "constant") stretches the probability mass in $(0, 1)$ to the range $(0, a)$ uniformly. Since $a$ is an integer, when we take “mod 1” (i.e. the fractional part) over this, we perfectly wrap this range $(0, a)$ on $(0, 1)$ and so the mass still remains uniform over $(0, 1)$, therefore $\text{frac}(a\theta) \sim U(0, 1)$Let,

\[\begin{align*} X_i &= \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } f(A_i) \in (1/3, 2/3) \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}, \forall i \in [1, N]\\ \end{align*}\]We take an example with a fixed $\theta$ to understand this transformation:

Let $A = \{1, 6, 2, 4, 5, 9\}$ and $\theta = 0.2$

| $A_i$ | $A_i \theta$ | $\text{frac}(A_i \theta)$ | $X_i = \mathbb{1}_{\text{frac}(A_i \theta) \in (1/3, 2/3)}$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 6 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1 |

| 4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0 |

| 5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0 |

This $\theta$ gave us only one value in $(1/3, 2/3)$ range, however since $\theta \sim U(0, 1)$ we would see each element of $A$ get transformed to be in $(1/3, 2/3)$ range with probability $1/3$.

So on average, how many elements of $A$ would be transformed to the $(1/3, 2/3)$ range? $\text{[Hint: Use the indicator random variable logic again, similar to what we did in Q1]}$

\[\begin{align*} \text{Let }X &= \bigl|\{A_i | f(A_i) \in (1/3, 2/3), \forall i \in [1, N]\}\bigr|\\ \Rightarrow X &= \sum_{i = 1}^{N}X_i\\ E[X] &= E[\sum_{i = 1}^{N}X_i]\\ &= \sum_{i = 1}^{n}E[X_i] \text{ [Using Linearity of Expectation]}\\ &= \sum_{i = 1}^{n}Pr(f(A_i) \in (1/3, 2/3))\\ &= \frac{N}{3} \end{align*}\]Since $E[X] = N/3$, there exists an instance of $X = x$ (and a corresponding a $θ^{\ast}$) where the subset of $\{X_i\}\text{’s} = 1$ is of size $\geq N/3$. Let this subset be called $B$, then:

\[\begin{align*} & |B| \geq N/3\\ \forall b \in B, & b\theta^{\ast} \in (1/3, 2/3)\\ \Rightarrow \forall b_1, b_2, b_3 \in B, & \text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast}) + \text{frac}(b_2\theta^{\ast}) \neq \text{frac}(b_3\theta^{\ast})\\ \Rightarrow & b_1 + b_2 \neq b_3 \end{align*}\]Note: The last step, $\text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast}) + \text{frac}(b_2\theta^{\ast}) \neq \text{frac}(b_3\theta^{\ast}) \Rightarrow b_1 + b_2 \neq b_3$ is NOT true in general, take the counter-example of $b_1 = 3, b_2 = 8, b_3 = 11$ and $\theta^{\ast} = 0.6$, then $\text{frac}(3 \times 0.6) + \text{frac}(8 \times 0.6) = 0.8 + 0.8 \neq \text{frac}(11 \times 0.6) = 0.6$, whereas we know trivially that $3 + 8 = 11$.

However, given $\text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast}), \text{frac}(b_2\theta^{\ast}), \text{frac}(b_3\theta^{\ast}) \in (1/3, 2/3)$, therefore the left-hand side of the expression can’t wrap-over / carry-forward a +1 and still hit the $(1/3, 2/3)$ range, therefore the last step holds.

Spoiler for more rigorous proof of the last step

Proof by contradiction: \begin{align*} b_1 + b_2 &= b_3\\ b_1\theta^{\ast} + b_2\theta^{\ast} &= b_3\theta^{\ast}\\ \text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast} + b_2\theta^{\ast}) &= \text{frac}(b_3\theta^{\ast})\\ \end{align*} Since $b_1, b_2, b_3 \in B$, we know that $\text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast}), \text{frac}(b_2\theta^{\ast}), \text{frac}(b_3\theta^{\ast}) \in (1/3, 2/3)$, therefore the left-hand side of the expression can't wrap-over / carry-forward a +1 and still hit the $(1/3, 2/3)$ ($\text{frac}(0.66 + 0.66) = 0.332 < 0.33$) \begin{align*} \Rightarrow \text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast}) + \text{frac}(b_2\theta^{\ast}) &< 1\\ \Rightarrow \text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast} + b_2\theta^{\ast}) &= \text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast}) + \text{frac}(b_2\theta^{\ast})\\ \text{frac}(b_1\theta^{\ast}) + \text{frac}(b_2\theta^{\ast}) &= \text{frac}(b_3\theta^{\ast}) \end{align*} Contradiction!Credits to Adhyyan Sekhsaria for flagging this missing step.

Ta-da again!!

[Re-read this proof a couple of times. If you have this nagging feeling: “that seems like a scam, but the proof works”, well that’s probabilistic methods for you]

Food for thought #1: What if $0$ is in $A$, does our claim break? Can you still come up with some lower bound on the size of $B$?

Food for thought #2: Try this extension of Q2: Given a set of positive integers $A$ of size $N$, show that there exists two disjoint subsets $B \subseteq A$ and $C \subseteq A$, such that:

What Next?

- MIT Lecture Notes: here, MIT Student Notes: here

- Covered as a subtopic in randomized algorithms courses: here and here

- The Probabilistic Method by Alon & Spencer

A final problem to ponder on

Maybe the two problems we discussed above, leave you with this feeling: “So the entire topic is just tricks around the expected value”. Well, here is a problem that would help you uncover one of many other tricks in the arsenal:

For any set $S$ of $10$ numbers all ranging from $1$ to $120$, prove that there must exist two different subsets of $S$ which have the same sum.

Weaker version: Let all the numbers of $S$ be in the tighter range of $1$ to $100$, what about now?

Spoiler

Weaker version can be done by Pigeonhole Principle, but the original version requires Chebyshev's inequality followed by the pigeonhole idea. Refer to Theorem 4.6.3 from the MIT Lecture Notes for the exact proof.-

1: We do not care if $X$ and $Y$ are independent or not. Incase they are independent then the statement is obvious, but interestingly enough it holds even when they are not independent. Proof is here ↩

-

2: I certainly could not, the proof we cover in this blogpost is the one mentioned here(Pg 23) ↩

-

3: The sum of the two smallest elements in $(1/3, 2/3)$ (i.e. $(1/3 + \epsilon) + (1/3 + \epsilon) > 2/3)$ would exceed the largest possible value allowed (i.e. $< 2/3$), so no triplet where $b_1 + b_2 = b_3$ can be formed. ↩